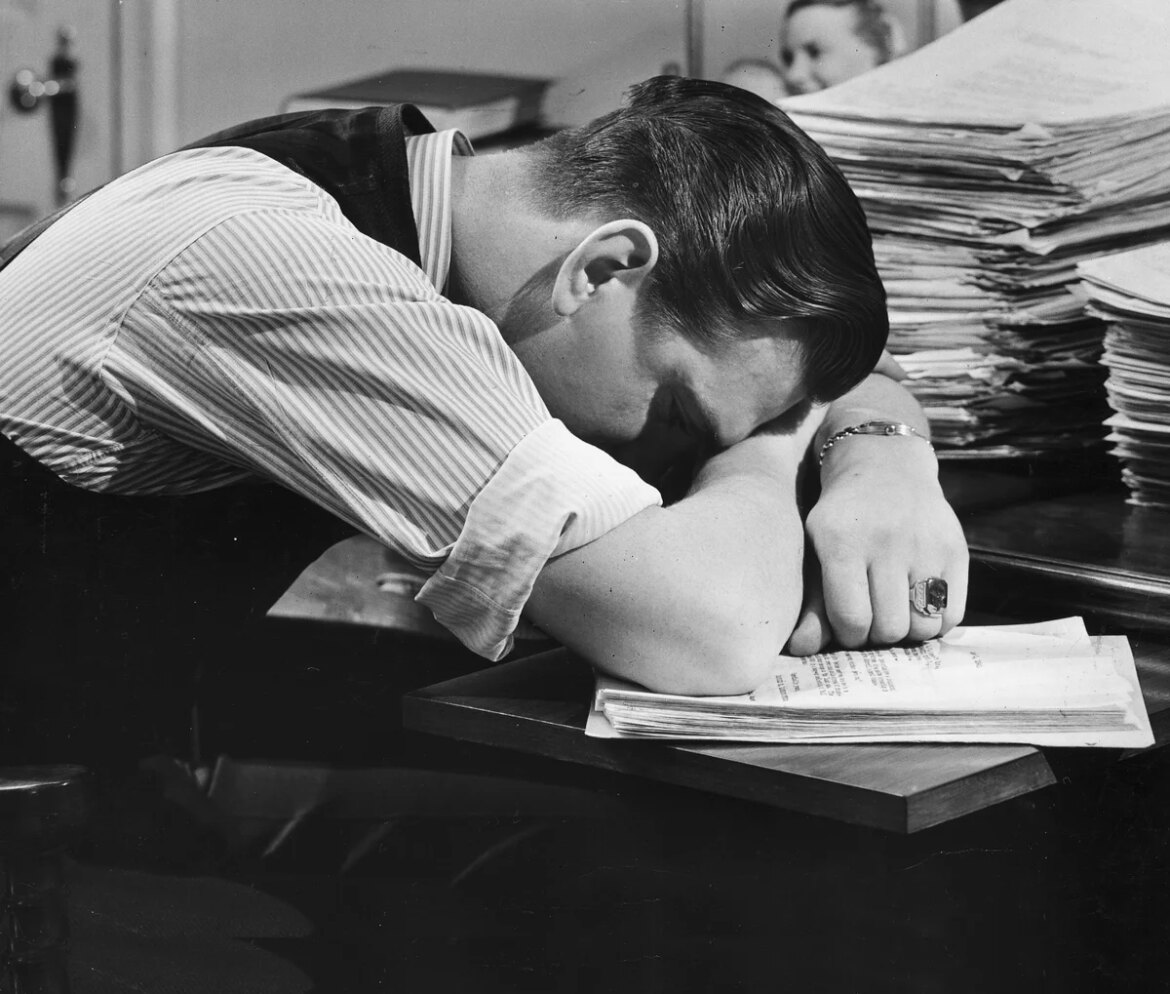

No one likes to do work that they find unpleasant. Who among us has not given up on difficult things like a tedious task, a deep clean of the fridge or a difficult conversation? The reason someone can’t get started isn’t just a failure of willpower: it’s rooted in neurobiology.

one in new paper published in current biology, Researchers have described a circuit in the brains of macaque monkeys that appears to act as a “motivation brake,” a discovery that may offer clues as to why people hesitate in making certain decisions.

“We were able to causally link a specific brain pathway to the ‘brake’ on motivation when individuals are faced with unpleasant tasks in daily life,” says study co-author Ken-ichi Amemori, an associate professor at the Institute for the Advanced Study of Human Biology at Kyoto University and a co-author of the study.

On supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism Subscribing By purchasing a subscription, you are helping ensure a future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In the study, researchers presented macaques with tasks: the monkeys would either receive a reward at the end of the task or receive the reward as well as a puff of air in their face. As one might expect, the monkeys took longer to perform the task when it meant taking an uncomfortable puff of air.

Then, using a technique called chemogenetics, whereby scientists can use drugs to control specific brain cells, the researchers suppressed a circuit between two brain areas called the ventral striatum and ventral pallidum – both known to be involved in motivation.

Once circuit activity was reduced, the monkeys were less hesitant to perform the task, even when they knew a gust of wind was coming. In other words, it appears that the “brakes” have been removed.

“We hope that understanding this neural mechanism will help advance our understanding of motivation in stressful modern societies,” Amemori says.

He and his team hope that these findings may one day inform treatments for psychiatric conditions that include motivations such as schizophrenia and depression. However, he also notes that interference designed to weaken “Breaks” should be approached with caution, if they can promote – on the contrary – taking unsafe risks.

It’s time to stand up for science

If you enjoyed this article, I would like to ask for your support. scientific American He has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most important moment in that two-century history.

i have been one scientific American I’ve been a member since I was 12, and it’s helped shape the way I see the world. Science Always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does the same for you.

if you agree scientific AmericanYou help ensure that our coverage focuses on meaningful research and discovery; We have the resources to report on decisions that put laboratories across America at risk; And that we support both emerging and working scientists at a time when the value of science is too often recognised.

In return, you get the news you need, Captivating podcasts, great infographics, Don’t miss the newsletter, be sure to watch the video, Challenging games, and the best writing and reporting from the world of science. you can even Gift a membership to someone.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you will support us in that mission.