Smaller models are becoming increasingly more capable and applicable to a variety of enterprise use cases. Plus, each new GPU generation packs dramatically more compute and memory bandwidth. outcome? Even under high-concurrent workloads, small LLMs often leave a large portion of GPU compute and memory bandwidth idle.

Our enterprise customers offer many such small language models on Databricks, with use cases like code completion, recovery, grammar correction, or specialized models, and we are constantly pushing GPUs to their limits. NVIDIA’s Multi-Process Service (mps) looks like a promising tool: it allows multiple inference processes to share the same GPU context, enabling their memory and computation operations to overlap – effectively squeezing far more work out of the same hardware.

We set out to rigorously test whether MPS delivers higher throughput per GPU in our production environment. We found that MPS provides meaningful throughput wins in these settings:

- Very small language models (≤3B parameters) with small-to-medium context (<2k tokens)

- Very small language models (<3B) in prefill workloads only.

- Engines with significant CPU overhead

The main explanations based on our ablation are twofold: at the GPU level, MPS enables meaningful kernel overlap when individual engines leave compute or memory bandwidth under-utilized – especially during attention-critical phases in smaller models; And, as a useful side effect, it can also reduce CPU bottlenecks such as scheduler overhead or image-processing overhead in multimodal workloads by splitting the total batch across engines, reducing the CPU load per engine.

What is MPS?

NVIDIA’s Multi-Process Service (MPS) is a feature that allows multiple processes to share the same GPU more efficiently by multiplexing their CUDA kernels on the hardware. As NVIDIA’s official documentation says:

Multi-Process Service (MPS) is an alternative, binary-compatible implementation of the CUDA application programming interface (API). The MPS runtime architecture is designed to transparently enable cooperative multi-process CUDA applications.

In simple terms, MPS provides a binary-compatible CUDA implementation within the driver that allows multiple processes (such as the inference engine) to share the GPU more efficiently. Instead of processes sequencing access (and leaving the GPU idle between rotations), their kernel and memory operations are multiplexed and overlapped by the MPS server when resources are available.

Scaling Landscape: When Does MPS Help?

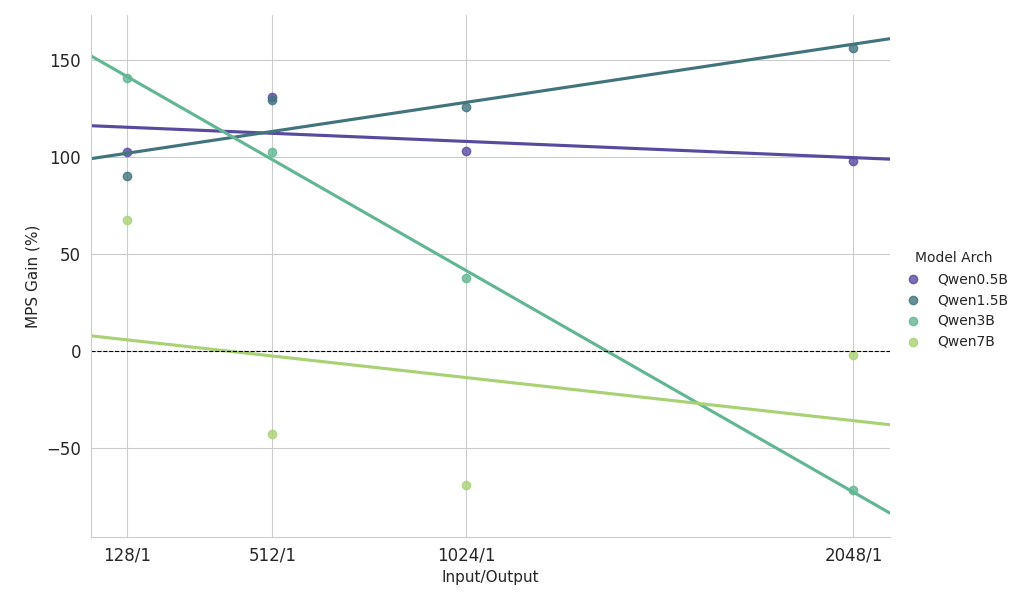

On a given hardware setup, effective utilization depends largely on model size, architecture, and reference length. Since recent large language models converge on similar architectures, we use the Qwen2.5 model family as a representative example to explore the impact of model size and context length.

The experiments below compared two identical inference engines running on the same NVIDIA H100 GPU (with MPS enabled) against a single-frequency baseline, using a fully balanced homogeneous workload.

Key observations from the scaling study:

- MPS provides >50% throughput uplift for small models with small contexts

- The benefit falls log-linearly as the context length increases – for the same model size.

- As model size increases, the benefits decrease rapidly – even in small contexts.

- For the 7B model or 2K reference, profits fall below 10% and eventually recession occurs.

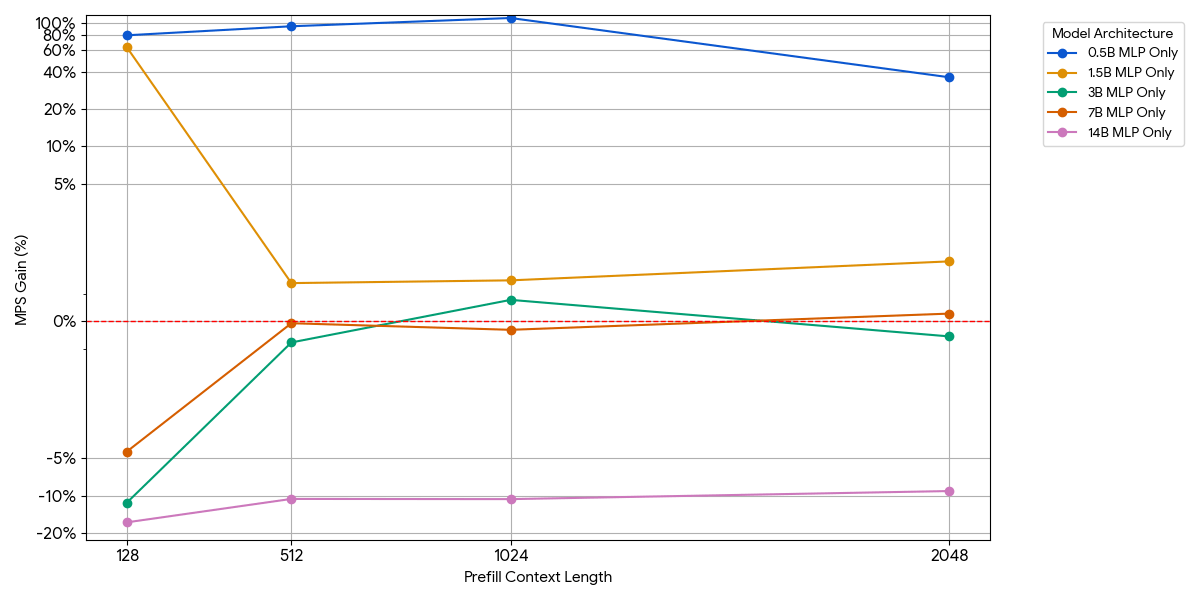

Key observations from scaling study on prefill heavy workloads

- Small models (<3B): MPS consistently provides throughput improvements of more than 100%.

- Medium-sized models (~3B): The benefits diminish as the context length increases, ultimately leading to performance degradation.

- Large models (>3B): MPS does not provide any performance benefits for these model sizes.

The scaling results above show that the benefits of MPS are most pronounced for low GPU utilization setups, small models, and compact context, which facilitate effective overlapping.

Benefits Analysis: Where Do MPS Benefits Really Come From?

To find out the exact reason, we broke down the problem with the two main building blocks of modern transformers: MLP (Multi-Layer Perceptron) layers and attention mechanisms. By isolating each component (and removing other complicating factors like CPU overhead), we can more accurately state the benefits.

GPU resources required |

|||

| n = reference length | prefill(calculation) | Decode (Memory Bandwidth) | decode (calculate) |

| mlp | But) | O(1) | O(1) |

| pay attention | O(n^2) | But) | But) |

Transformer consists of attention and MLP layers with different scaling behavior:

- MLP: loads weight once; Processes each token independently -> constantly consumes memory bandwidth and counts per token.

- Note: KV loads the cache and calculates the dot product with all previous tokens → linear memory bandwidth and calculations per token.

With this in mind, we performed targeted resection.

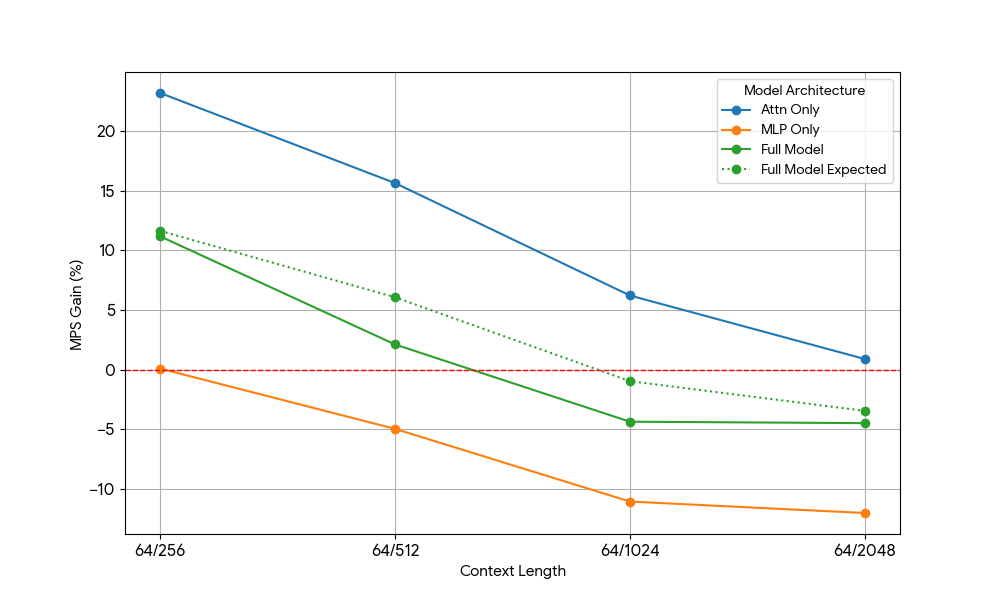

MLP model only (removed)

For small models, the MLP layer cannot saturate the computation even with more tokens per batch. We isolated the effect of MLP by removing attention inhibition from the model.

As shown in the figure above, the benefits are modest and quickly disappear. As model size or context length increases, a single engine already saturates the computation (more FLOPs per token in larger MLPs, more tokens with longer sequences). Once an engine is compute-bound, there is almost no benefit from running two saturated engines – 1 + 1 <= 1.

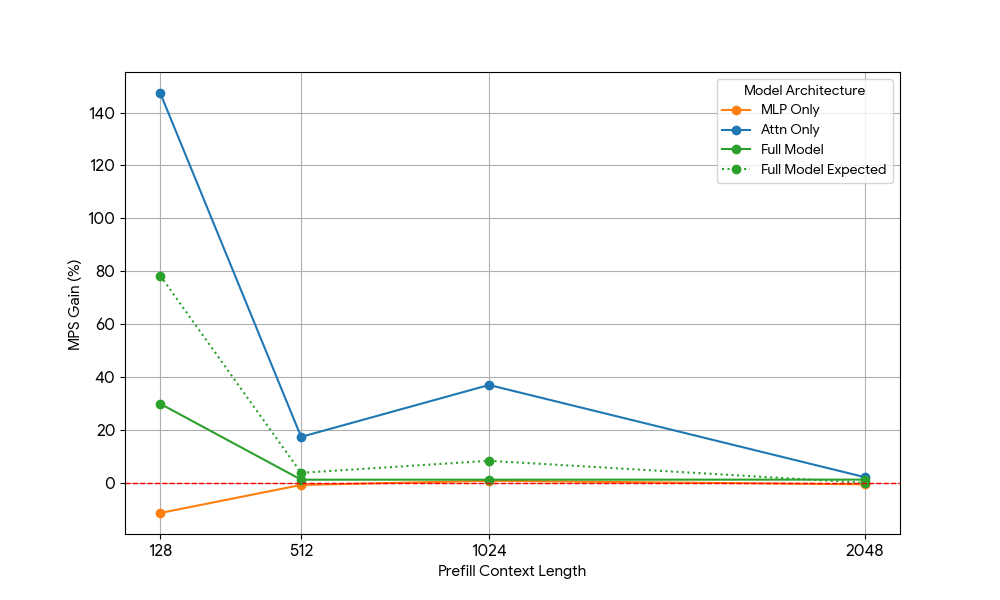

Attention-only model (MLP removed)

After seeing limited gains from MLP, we took the Qwen2.5-3B and measured the attention-only setup analogously.

The results were surprising:

- The attention-only workload shows a significantly larger MPS gain compared to the full model for both prefill and decode.

- For decode, the benefits are linearly decreasing with context length, which is consistent with our expectation that in the decode phase, resource requirements for attention increase with context length.

- For prefill, the gain dropped more rapidly than for decode.

Does the MPS gain come entirely from attention gain, or is there some attention MLP overlapping effect? To study this, we calculated the full model expected profit as a weighted average of only attention and MLP, including their contribution to wall time. This full model expected gain is essentially the gain from Attn-Attn and MLP-MLP overlap, while it does not account for Attn-MLP overlap.

For the decode workload, the full model expected gain is slightly higher than the actual gain, which indicates limited impact of ATN-MLP overlap. Furthermore, for the prefill workload, the actual full model gain is much lower than the expected gain from seq 128, a hypothetical explanation could be that unsaturated attention kernels have less opportunities to overlap because the other engine is spending a significant fraction of the time doing saturated MLP. Therefore, most of the MPS gain comes from the 2 engines, whose concentrate is unsaturated.

Bonus benefit: recovering GPU time wasted in CPU overhead

The above ablations are focused on GPU-bound workloads, but the most severe form of underutilization occurs when the GPU remains idle waiting for CPU work – such as the scheduler, tokenization, or image preprocessing in multimodal models.

In a single-engine setup, these CPUs directly waste GPU cycles. With MPS, whenever the first engine is blocked on the CPU, the second engine can take over the GPU, turning dead time into productive computation.

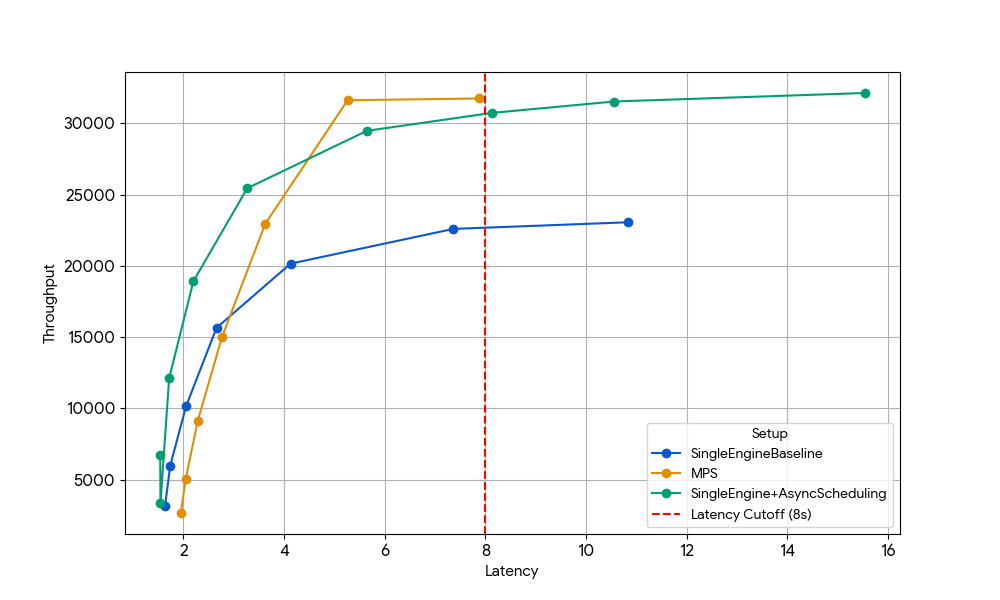

To isolate this effect, we deliberately chose a regime where the earlier GPU-level advantages disappeared: Gemma-4B (a size and context length where attention and MLPs are already well saturated, so kernel-overlap benefits are minimal).

At a latency of 8s, the baseline single engine (blue) scheduler is limited by CPU overhead, which can be lifted by enabling asynchronous scheduling in the VLLM (green line, +33% throughput) or by running two engines with MPS without asynchronous scheduling (yellow line, +35% throughput). This nearly identical gain confirms that, in CPU-constrained scenarios, MPS can reclaim essentially the same idle GPU time that async scheduling eliminates. MPS can be useful because vanilla VLLM v1.0 still has CPU overhead in the scheduler layer where optimizations like asynchronous scheduling are not fully available.

A bullet, not a silver bullet

Based on our experiments, MPS can achieve significant benefits for small model inference in some operational areas:

- Engines with significant CPU overhead

- Very small language models (≤3B parameters) with small-to-medium context (<2k tokens)

- Very small language models (<3B) in prefill-heavy workloads.

Outside of those sweet spots (for example, 7B+ models, long-reference >8k, or already compute-constrained workloads), GPU-level benefits cannot be easily captured by MPS.

On the other hand, MPS also introduced operational complexity:

- Additional moving parts: MPS daemon, client environment setup, and a router/load-balancer to split traffic across engines

- Increased debugging complexity: no isolation between engines → a memory leak or OOM in one engine can corrupt or kill all the others sharing the GPU

- Monitoring burden: Now we have to monitor daemon health, client connection status, inter-engine load balancing, etc.

- Critical failure mode: Because all engines share the same CUDA context and MPS daemon, a misbehaving client can corrupt or starve the entire GPU, affecting every co-located engine instantly.

In short: MPS is a fast, specialized tool – extremely effective in the narrow regimes described above, but rarely a general-purpose victory. We really enjoyed pushing the limits of GPU sharing and finding out where the real performance rocks are. There is still a huge amount of untapped performance and cost-efficiency in the entire inference stack. If you’re excited about making distributed service systems, or LLM, production 10x cheaper, we’re hiring!

Author: Xiaotong Jiang